|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Featured person

Recently added |

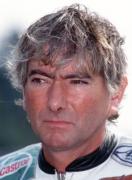

Joey Dunlop (1952 - 2000): |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Joey Dunlop |

William Joseph Dunlop (he was said to have disliked all his sobriquets except "Joey") was born in Unshinagh, a townland near Dunloy, in North Antrim, second of seven children of a motor mechanic, and educated at Ballymoney High School. Initially he thought of a military career, but when, at the age of sixteen, he bought his first motorcycle, he became impassioned by motorcycle racing and his employment patterns came to be dictated by the need to finance this interest: his jobs included at various times diesel fitter, lorry driver, steel erector, roofer, and pub-owner.

Motorcycle racing competitions in Ireland are often run on ordinary public roads, miles-long stretches of which are closed off to provide racing routes, all over the countryside. These contrast with purpose-built racetracks, known as short circuits, whose safety features are continually updated and improved. The latter are more common in England, whereas Irish and especially Northern Irish racing are often (though not exclusively) run on the former, which by their very nature are far more dangerous.

Joey Dunlop competed in both arenas - his first ever race was on a short circuit organised by the Motor Cycle Road Racing Club of Ireland at the Maghaberry airfield circuit near Moira, Co. Armagh, in 1969 - but preferred and was even more successful at road racing, which, given the nature and terrain of the courses, raced over at speeds well in excess of 100 mph, could be highly dangerous and there were many accidents involving serious injury and fatalities. Dunlop first competed at a closed-road race in the 1970 Temple 100, held on the Saintfield circuit in County Down. An influence on him was the local racer Mervyn Robinson, who also happened to be the brother of Dunlop's childhood girlfriend, Linda; she and Dunlop were married in 1972. Dunlop, Mervyn Robinson, and another North Antrim racer, Frank Kennedy, came to be known as the "Armoy Armada" (Armoy being another town in North Antrim).

Dunlop took several years to become a regular winner, but when he did, he was prolific. At the world-famous Isle of Man TT, whose internationally-renowned Snaefell Mountain Course is notoriously dangerous, run as it is at three-figure speeds over 37 miles of narrow, winding streets, roads and rural lanes flanked by stone walls and buildings, he won a total of 26 races over his career; the next-most regular winner, though still racing (2010), has won a "mere" 16. The two most prestigious Irish road races are the North-West 200 (that is, north-west County Londonderry), in which Dunlop won thirteen races, and the Ulster Grand Prix, at which he won twenty-four times: in the Formula One TT World Championship his record was 3rd place in 1981, 1st place every year between 1982 and 1986, and 2nd place 1987-1989; he competed also at events in England, France, Germany and Hungary. All-in-all he had over 160 wins in the course of his career.

He raced a wide range of motorcycles, both makers and models, which he normally serviced and maintained himself. These included the Aermacchi 350; the Yamsel: 250, 350 and 500; the Sparton 50; the Yamaha 250, 350, 500 and 750; the Suzuki 200, 500, 1000; the Benelli 550; the Devimead Honda 812; the Honda 125, 250, 400, 500, 600, 750, 858, 900, 920, 1000 and 1023.

Within the motorcycle racing world Dunlop received numerous awards and honours. He was seven times Enkalon Rider of the Year, five times Road Racing Ireland Rider of the Year, in 2000 was honoured by Manx leaders with a replica Sword of State inscribed "King of the Mountain", and in October was awarded the prestigious Médaille de Bronze of the Fédération Internationale Motocycliste, the world governing body of motorcycle sport, at their October 1993 congress in Dublin, as "Champion de Courses sur Route" or road racing champion. He had been appointed MBE in 1985 for his services to motorcycling, was awarded the Freedom of Ballymoney in 1993 and appointed OBE in 1995, partly for his record breaking TT success but also in recognition of his humanitarian activities. A close friend described how Dunlop reacted to hearing stories of impoverishment in Balkan countries, especially what became highly disturbing accounts of conditions in such institutions as the notorious Romanian orphanages, about which he had heard from the father of a nurse who was working in Romania; he simply packed his large van with all sorts of commodities desperately needed, whether food, clothes, toys, nappies, baby wipes, or wheelchairs, and drove off to eastern Europe on his own. It was said that he rarely told people he was going - he hardly even told his wife. These trips were not without risk, in the Balkans of the 1990s - he also made humanitarian trips to Albania and, perhaps most dangerous of all, Bosnia-Hercegovina.

He was well-known as being totally uninterested in any trappings of success or fame, eschewing first class flights and five star hotels, a shy man who often preferred his own company and never sought any limelight. Even when travelling to racing tournaments, he would live on beans and cold soup and sleep in the back of his van beside his motorcycles. A hotel owner in Tallinn, Estonia had a room permanently reserved for him (and even named it after him), but he usually kept to his van. One fellow-racer described how Dunlop would collect his winnings on the trips, then just see someone with children and give them money and tell them to buy something for what he referred to as the "wains" (children).

Motorcycle racing, most especially road racing, has always been a dangerous sport. Dunlop survived two serious accidents. On Good Friday, 24 March 1989, he was competing in the Eurolantic Motor Cycle Challenge meeting at the Brands Hatch circuit in Kent when he was involved in a crash with a Belgian rider, Stephane Mertens. Dunlop suffered multiple injuries, which included a broken leg, fractured ribs, and a broken wrist. He needed several months to recuperate enough to race again. His second serious crash occurred at the 1998 Tandragee 100 meeting, in County Armagh. In a high-speed crash, he lost the tip of a finger of his left hand, and sustained a cracked pelvis, a broken collarbone, and a broken bone in his right hand. His brother Robert, also a champion motorcycle racer, was seriously injured in an accident in 1994. But far worse, of the original "Armoy Armada", their dangerous sport claimed the lives of Frank Kennedy in 1979 and of Mervyn Robinson in 1980, both in accidents at the North West 200 (the same day as Kennedy, 26 May 1979, the North West 200 claimed another outstanding racer, Tommy Herron, of whom Dunlop was a great fan).

Tragically, Dunlop was to suffer the same fate. At a competition in Estonia on 2 July 2000, he had won two races and was leading a third when, in wet conditions, his motorcycle left the track and crashed, killing him instantly. His funeral took place on 7 July at Garryduff Presbyterian, his local Church. Thousands of mourners attended and the service was carried live on television. Government ministers from London, Belfast, and Dublin were present. A joint statement was issued by the Northern Ireland First Minister David Trimble and the deputy First Minister Seamus Mallon, which summed him up thus: "Joey was a brilliant sportsman, a true man of the people, and a wonderful ambassador for Northern Ireland." He was voted the fifth greatest motorcycling icon ever by Motorcycle News in 2005, and the most successful overall rider at the Isle of Man TT races each year is awarded the Joey Dunlop Cup.

Dunlop, was survived by his wife, their three daughters and their two sons. On 15 May 2008, his younger brother Robert, the champion motorcycle racer, was killed in an accident during practice for the North West 200. He was also given a funeral at Garryduff and was laid to rest beside his elder brother. In 2006 the brothers had each been awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of the University by the University of Ulster at Coleraine, part of whose campus abuts the North West 200 course (at what is known as "University Corner"). Joey Dunlop's posthumous degree was accepted by his elder son, Gary; statues were raised to him at Murray's Motorcycle Museum on the Isle of Man, and in Ballymoney: at the unveiling in the Joey Dunlop Memorial Garden, the Mayor summed up Dunlop's character and impact thus: "The sculpture is a fitting lasting tribute to Joey, who, unaffected by the world success which his motorcycling career brought him, remained the quiet, cheerful, family man from Ballymoney, a characteristic which endeared him to all."

On 16 January 2015, at the conclusion of an online poll organised by the Belfast Telegraph, he was declared Northen Ireland's "Greatest Sports Star Ever".

| Born: | 25 February 1952 |

| Died: | 2 July 2000 |

| Richard Froggatt |

| Acknowledgements: Wesley McCann |

Home | Our Policies | Plaques | Browse | Search | Sponsors | Links | Help | Contact

Privacy & Disclaimer | Cookie Policy | Site Map | Website Design By K-Point

© 2024 Ulster History Circle